More “Hidden Figures” Discovered at the University of Chicago

Posted on Jan 17, 2024 | Comments 0

On his first trip to the U.S. in 1921, Albert Einstein visited Yerkes Observatory, located in Wisconsin and run by the University of Chicago. Those present gathered for a photograph with the telescope. Nearly a century later, members of a team reviewing historical materials to preserve the history of the observatory stopped and looked at it in surprise. There were a lot of women in the photograph.

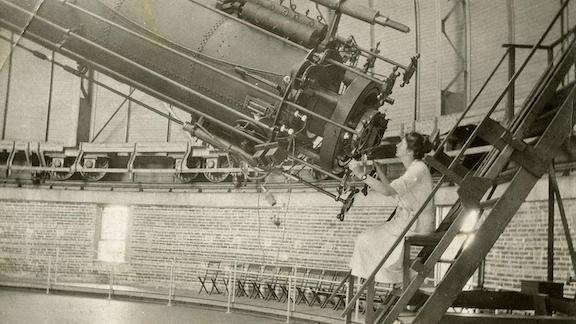

Someone had written the women’s names on the photo and current day researchers have identified more than 100 women who worked at the facility. The records revealed they weren’t solely secretaries or “computers” who primarily solved equations. In an era when few women were able to be professional scientists, these women performed astronomical observations, analyzed data, collaborated with researchers around the world, and published papers.

Located in southern Wisconsin on the shores of Lake Geneva, Yerkes Observatory was constructed in 1897 under the leadership of eminent UChicago astronomer George Ellery Hale. Yerkes’ handsome terra-cotta building housed the largest refracting telescope in the world, and for decades, the observatory attracted astronomers from around the globe. The astronomers at Yerkes took thousands of images of the night sky and transferred them onto chemically treated glass plates. At the time, this was a new technology, and it was revolutionizing astronomy. For the first time, extremely precise images of the sky could be stored for future reference. Over the century Yerkes operated, scientists created more than 175,000 of these glass plates.

Yerkes had several things that set it apart for women who wanted to do science. It was near a train line from a major city, Chicago, so women could travel alone easily and safely; and for decades, it had a director who was willing to hire them. Edwin B. Frost headed the Yerkes Observatory from 1905 to 1932. An accomplished astronomer, Frost was also a self-identified suffragist, and the team has theorized that his politics played a role in making Yerkes Observatory an unusually welcoming place for women in science.

When the observatory closed, much of the archival material from Yerkes — photos, personnel records, logbooks, correspondence and more — was transferred to the University of Chicago Library. There, Andrea Twiss-Brooks, director of humanities and area studies and others began sorting through it. “We quickly recognized how rich a historical source it was,” Twiss Brooks explained. She and her colleagues launched a research project to find out more about the women of Yerkes.

Filed Under: Research/Study • Women's Studies